Martin Freeman and Liberia

Martin Freeman's Beliefs on Emigration

Martin Freeman advocated for the emigration of African Americans to Liberia, more formerly called the Colonization Movement. He believed that it was an advantageous solution which would allow African Americans to have the best chance of living a free, fulfilled life. To Freeman, Africa presented “a very important and desirable field for civilizing and missionary labors – the resources of an entire continent to be developed, the energies of a whole race to be directed by civilization and controlled by the benign influences of Christianity” (“Emigrants Sent”). Freeman frequently noted within his writings that he understood that it was his duty, as a father and husband, to create the best situation for his family: Africa. Freeman advocated that the Colonization Movement embraced the entire future of the colored race and therefore was necessary to embrace this prospect for the good of his race. He also stressed that the emancipation of African Americans did not lead to the free, prosperous life it promised, but rather one that possessed symbolic bondages due to his ethnicity.

The Importance of Education

Freeman preached that the education of the free African American served as a necessity in order to alleviate many of the injustices that still plagued the African American community. Freeman defined education as the “harmonious development of the physical, mental, and moral powers of man” (“Original work of the Free Colored People”). Freeman stressed that education of black Americans in the United States was suppressed while the education of African Americans in Liberia could be freely instituted. In Freeman’s writings, he believed that his “colored people” must educate their children that slavery is a sin and thereby prevent the psychological subordination of the African American to the white American. Thus, Freeman advocated the education of African Americans in Liberia to promote a positive outlook on their race by encouraging self-respect and self-reliance, which were at the basis of any “just harmonious development of mind” (“Original Work of the Free Colored People”).

Financial Assistance

In his letter in 1863 to Joseph Tracy, Freeman regretted not going to Africa as a missionary after leaving school. When he wanted to go to Liberia later in life he was poor and needed financial assistance. He could not become a missionary in 1863 as his reasoning for becoming a missionary would be under question. In his letter, Freeman told Tracy “I stand ready to labor in any department of that vast field, as a minister, missionary to the interior, teacher of whatever my hands find to do, that they can do well” (Freeman 7-14-1863).

The Preparations for the Voyage to Africa

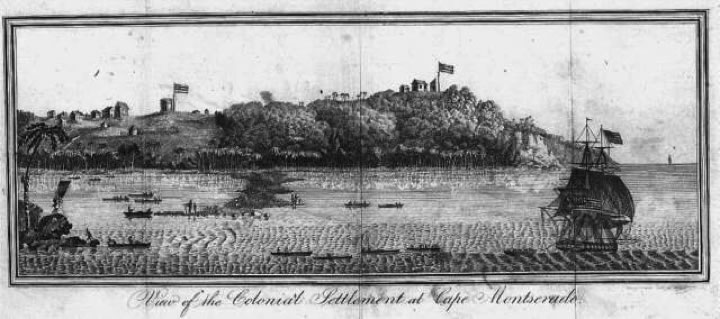

In 1863, Martin Freeman was offered the position of chair of Mathematics and Natural Philosophy at Liberia College in Monrovia, an opportunity he had been waiting for many years(“Departure of Emigrants”). He gladly accepted after voluntarily resigning as President of Avery College in Pennsylvania but his departure to Africa was delayed for almost a year. In the meantime, Freeman traveled throughout New England on a lecture tour to defray the costs of the trip (Buckeye 6). In the fall of 1864, Martin Freeman finally got his chance to go to Liberia with the help of Joseph Tracy. On September 13, Freeman set sail from New York on the ship of Thomas Pope accompanied by his wife Louisa, their two children Cora and John, and family aide Matilda. Upon arrival, Freeman felt a great sense of accomplishment but quickly realized that Liberia was not as he imagined. He was taken back by the major differences in culture including voodoo practices and corruption in the government. He compared the civilization of Liberia to that of the Old Slave South in the United States (Freeman 8-2-1880).

Liberia College and Expectations

While at the college, he was overworked as his colleagues were frequently absent and found that his students were often unprepared (Buckeye 6). Even more, he was frustrated by the lack of students as the number shrunk as low as four at one point. This was evident in his letter to the Board of Trustees of the College in 1886 regarding the condition of the college which also expressed his frustration with the continuation of repairs to college buildings at a time when the college was lacking funds, finding it “inopportune and inexpedient” (Freeman 11-30-1886). Although Liberia did not live up to his expectations, Freeman still found it to be a positive experience and a better alternative to life in the United States. In a letter to his friend, Charlotte Chaffee, in 1880 he shared the following, “The Negro in Africa is a man; and though he may be a bad man there is scope and hope for such improvement as will make him a good man, while in the U.S. the difficulty may almost impossibility of the attainment of a full and perfect manhood for the black man is a bar to all further improvement” (Freeman 8-2-1880).

Martin Freeman in America and His Declining Health

In 1887, Freeman returned to the United States for the first time in nearly two decades for health reasons. He planned to return to Liberia quickly but medical complications furthered his stay in the States. Upon return, he hoped that he would not have to continue teaching at the College. In a September letter, Freeman expressed his displeasure with his role at the college, writing that he would be very glad if any man were to relieve him of his duties (Freeman 9-10-1887). Still, it is clear that he would rather be in Liberia than America as his letter one month later reveals, “Life, within the limits prescribed for the Negro in this Country, is not worth living” (Freeman 10-18-1887). Eventually Freeman traveled back to Liberia and continued working at the college.The Board pleaded with him to stay, finding his contributions to the school irreplaceable and in January 1889 he was elected President of the College. His health was rapidly declining at the time and roughly two months later, on March 13, 1889, Martin Freeman died and was buried by his wife in Liberia, “the land of his ancestors” (Buckeye 7).

The Legacy

Over two hundred years after his death, Martin Freeman is still remembered as a pioneer to the colonization of Liberia and an advocate for higher education for African-Americans. From his days at Middlebury College, Freeman showed the potential to make a positive impact on the lives of those around him. Prior to speaking at Middlebury College in 1863, College President Benjamin Labaree introduced him as a man who “undoubtedly surpassed the expectations of all who heard him” and whose future will “shed a brighter luster” on the college than any of his peers (Midd Register). Freeman was the first African-American to be accepted to and graduate from Middlebury College; however, Freeman wanted to do more with his life. As an advocate of the separation of races, Freeman strived to bring the African-American race to the full status of mankind and thought that the emigration to Liberia would be the best option (Emigrant Sent). In the 51st annual report, the speaker explains how Freeman was offered a job as a professor in the United States with a favorable salary that would entice him to stay. However, Freeman felt the need to return to Liberia to finish his work. On March 13, 1889, Martin Freeman passed away as his health failed him. In Arthur Barclay’s letter to J.C. Braman, Barclay praised Freeman as a man who “impressed all by his unassuming manner, his capacity, his blameless life and his entire devotion to the cause of education” (Letter 3-13-1889). Freeman’s work ethic and dedication to helping African Americans has been emulated by those who have followed and will continue to be for years to come.